Unpacking The Face Split Incident 2009 Story: Digital Geometry Challenges And The Original Video

Do you ever wonder about those frustrating moments in digital creation, the ones that make you pull your hair out? Well, way back in 2009, a particular set of challenges in 3D modeling software, often involving what looked like a "face split," became a real point of discussion for artists and designers. It wasn't some dramatic real-world event, but rather a common, yet vexing, technical hurdle that many encountered. This story, in a way, is about those perplexing digital geometry problems that could make a perfect model suddenly seem to tear apart, or just refuse to behave correctly.

People were, you know, constantly searching for answers, trying to figure out why their carefully crafted digital surfaces just wouldn't cooperate. It felt like, at times, the software itself was playing tricks, especially when trying to select faces or get them to display just right. This era, in some respects, saw many artists grappling with the very foundations of 3D object creation, and looking for clarity.

The "face split incident 2009 story original video" really refers to the collective experience of these problems and the helpful tutorials or demonstrations that emerged to show how to fix them. These videos, which were, like, so important then, aimed to demystify why a face might appear split, black, or simply not selectable. They offered a kind of shared solution to what felt like a universal headache for anyone working with digital faces and their tricky properties.

Table of Contents

- Understanding the Digital Face Split Phenomenon

- The Frustration of Face Selection in 2009

- Flipping Normals and the Mystery of Black Faces

- Creating and Orienting Faces from the Ground Up

- Texture Alignment and Void Cutting Complications

- Placement and Workflow for Avoiding Face Issues

- General Component Manipulation and the Learning Curve

- Frequently Asked Questions About Digital Face Issues

- Finding Solutions and Moving Forward

Understanding the Digital Face Split Phenomenon

The "face split incident 2009 story original video" is really about a period when 3D artists, particularly those new to software like Maya or 3ds Max, often ran into what felt like fundamental problems with their digital models. It wasn't, you know, a literal split of a real face, but rather an issue where the geometric "faces" of a 3D object would behave unexpectedly. This could mean they wouldn't select right, or they'd show up black, or maybe they'd just refuse to orient themselves in the way you wanted. It was, in a way, a common pain point for many creators, and a lot of the discussion around it centered on finding reliable fixes.

The Frustration of Face Selection in 2009

One of the most immediate frustrations that contributed to the "face split incident" feeling was, honestly, the simple act of trying to pick out a specific face on a model. Many artists would try to select faces, but the software just wouldn't pick the ones they wanted. This could be incredibly annoying, especially when you're just starting out and trying to get a handle on how these programs work. It's almost like the software had a mind of its own, refusing to cooperate with basic commands.

When Faces Just Wouldn't Select

Imagine, if you will, being completely new to a 3D modeling program, and you're just trying to select a part of your creation. You click, and click again, but it simply won't select the face you're aiming for. This problem was a rather common occurrence for many, and it often led to a lot of head-scratching. People would search everywhere for a solution, feeling quite lost because this basic function seemed broken. It really highlighted how different the digital world could be from what you might expect, and how important precise selection is for any kind of detailed work.

The Role of Hosted Families and Their Faces

A big part of why faces could be so tricky involved something called "families that are hosted to a face." This means that certain elements or components in a 3D scene would attach themselves directly to the surface of another object. If that underlying face wasn't quite right, or if its properties were off, the hosted "family" would also misbehave. So, it became necessary to ensure these host faces were perfectly aligned and correctly formed. This interdependence could, you know, create a domino effect of issues if the foundational faces weren't solid.

Flipping Normals and the Mystery of Black Faces

Another common symptom of the "face split incident" was when parts of a model would just show up black, or maybe a very dark shade, instead of the expected gray or textured appearance. This was usually a dead giveaway that something was off with the "normals" of a face. Normals are, basically, invisible lines that tell the software which way a face is pointing, and if they're flipped inwards, the face won't catch light properly, making it look dark or even invisible from certain angles. This was a very common visual glitch that could make a model look broken.

Maya Hotbox Changes and Face Orientation

Around 2009, software like Maya saw some changes in its interface, and one particular point of confusion was how to flip faces when the "normals menu" was removed from the "hotbox." This change, you know, left many artists wondering how to perform a really basic, yet crucial, task. Getting the face orientation right is absolutely vital for proper rendering and avoiding those strange dark patches that look like parts of your model are missing or "split." It was a slight shift in workflow that caused a lot of people to search for new methods.

Getting the Correct Face Display

The goal, of course, was always to get the correct face to show up, not to show black, but to show gray, or whatever color or texture it was supposed to have. This meant ensuring that the face's normal was pointing outwards, towards the viewer. If it was pointing inwards, it would appear dark, almost like a void. Solving this was often a key step in resolving what looked like a "face split" problem, as a dark face can certainly give the impression of a hole or a broken surface. It was, quite simply, a visual cue that something needed fixing.

Creating and Orienting Faces from the Ground Up

The very act of building geometry could also lead to issues that felt like a "face split." If you were trying to create a face from a set of vertices, for example, and you didn't do it quite right, you could end up with a malformed or "open" surface. This kind of foundational problem would then cascade, affecting anything you tried to do with that particular part of the model. It was, in a way, about getting the basic building blocks correct from the very start.

Building Faces from Vertices in 3ds Max

A common question found in 3ds Max modeling forums around that time was about how to create a face from vertices. This seemingly simple task could be surprisingly tricky if you weren't familiar with the precise steps or if your vertices weren't perfectly aligned. Incorrectly formed faces could lead to rendering glitches or, you know, make it impossible to apply textures properly. It was a fundamental skill that, if not mastered, could definitely contribute to the overall "face split incident" experience, making models look incomplete or broken.

Face-Based Family Orientation Challenges

The orientation in a face-based family is based on the host, so if you place the family on a wall in the project, then the plan presentation set in the family is the front elevation. This means that if the host face itself was oriented incorrectly, or if the family wasn't set up to understand that orientation, the placed object would appear rotated or flipped. This could, you know, lead to a fixture appearing on the wrong side of a wall, or upside down, which certainly feels like a digital "split" from what was intended. It's a rather subtle point that could cause a lot of confusion.

Texture Alignment and Void Cutting Complications

Even if the geometry of your faces was perfect, the way textures were applied could still make it seem like there was a "face split." If textures weren't aligned correctly, or if they were rotated oddly, the visual effect could be quite jarring. Furthermore, the act of cutting holes or voids into existing geometry presented its own set of challenges, often leading to open edges or unintended gaps if not done with precision. These were, in a way, advanced problems that still fed into the overall "incident."

Modifying Texture Alignment Face by Face

Once you had your model, you could then modify texture alignment and rotation face by face. This gave artists a lot of control, but it also meant that if one face's texture was off, it could look very odd compared to its neighbors, almost like a visual "split" in the pattern. Learning to fine-tune these settings was a part of mastering the software, and it required careful attention to detail. It's like, a very precise kind of work that can make all the difference in how a model looks.

Cutting Geometry with Void Families

Many artists wanted to create a void family allowing them to cut some geometry into the project environment. They would not want to use the "model in place" feature because it is a void that they needed to reuse. The challenge here was creating a void that cleanly cut through existing geometry without leaving behind messy edges or, you know, creating actual gaps that looked like a "split" in the surface. This required a good grasp of boolean operations and family creation, and it was a common source of frustration if the cuts weren't clean.

Placement and Workflow for Avoiding Face Issues

Beyond the direct manipulation of faces, the way objects were placed and the overall workflow adopted by artists also played a role in avoiding or causing "face split" type incidents. Correct placement, especially for objects hosted to surfaces, was key to maintaining proper orientation and preventing visual anomalies. It was, in some respects, about developing good habits and understanding the underlying logic of the software.

Correcting Orientation with Face Hosting

Placing objects using "face hosting" was often the solution to getting a fixture to flip to the correct orientation in a ceiling plan, for instance. This method ensured that the object would align itself properly with the surface it was placed on, preventing it from appearing upside down or misaligned. It was a useful technique that, you know, helped avoid those frustrating moments where a light fixture, say, would be pointing into the ceiling instead of down. It’s pretty important for keeping things looking right.

Using Reference Planes for Precise Placement

Without using the reflected ceiling plan, a good method for accurate placement was to draw a reference plane from an elevation view. This provided a precise guide for placing objects, helping to ensure they were positioned correctly in 3D space. Accurate placement, of course, minimizes the chances of objects intersecting awkwardly or, you know, creating visual glitches that might resemble a "face split" due to overlapping geometry. It's a rather fundamental technique that helps keep your models clean.

General Component Manipulation and the Learning Curve

Overall, a lot of the "face split incident 2009 story original video" comes down to the general learning curve of moving between different 3D software packages. Someone trying to learn Maya after coming from 3ds Max, for example, might find it hard to locate basic functions like moving an object, a vertex, or a face. This kind of foundational confusion could easily lead to accidental errors that result in, you know, geometry problems that look like splits or tears. It's a natural part of learning new tools, and finding those "original videos" was often the key to figuring things out.

Frequently Asked Questions About Digital Face Issues

People often had similar questions when dealing with these tricky digital face problems. Here are a few common ones that might have appeared in forums or search queries around that time:

How do I fix a black face on my 3D model?

Often, a black face means its "normal" is pointing the wrong way. You typically need to select the face and use a "flip normal" or "reverse normal" command within your 3D software. This will make the face visible and correctly lit, rather than appearing dark or hidden. It's a very common fix for this particular visual issue, and, you know, it often clears things right up.

Why can't I select specific faces on my 3D object?

There could be several reasons why you can't select faces. Sometimes, another object might be in the way, or the face might be part of a group or component that needs to be "unlocked" or "edited" first. It's also possible that the face itself is corrupted or malformed. Checking your selection filters and object hierarchy is a good first step, and, you know, sometimes it's just about trying a different selection method. For more help, learn more about 3D modeling selection techniques on our site.

What are "normals" in 3D modeling and why are they important?

Normals are, basically, invisible lines that extend perpendicularly from the surface of a face. They tell the software which way the face is "facing." They are important because they determine how light interacts with the surface, affecting its appearance, and they also dictate how certain modifiers or operations behave. Incorrect normals can lead to rendering errors, shading problems, or, you know, even issues with exporting your model. It's a rather fundamental concept for proper 3D geometry, and understanding them is pretty crucial for good results. You can find more details on understanding 3D geometry basics.

Finding Solutions and Moving Forward

The "face split incident 2009 story original video" really encapsulates a period of learning and adaptation for many digital artists. It highlights how common technical hurdles can become shared experiences, driving people to seek out and create helpful resources. These "original videos" were, you know, often simple tutorials that showed someone working through the problem, step by step, which was incredibly valuable at the time. They provided practical guidance on issues like selecting faces, flipping normals, or correctly orienting hosted families, helping countless creators overcome what felt like insurmountable obstacles in their 3D work. It's pretty cool to think about how those early shared struggles led to so much collective knowledge.

Even today, while software has certainly evolved, the fundamental principles of working with digital faces remain. Understanding how to manage normals, how to properly host elements, and how to create clean geometry is still, you know, absolutely vital for any 3D artist. The lessons learned from those early "face split" moments continue to inform best practices in the field. If you're encountering similar issues, remember that the answers often lie in those core concepts of digital geometry. For more insights into these topics, you might find external resources on 3D modeling basics helpful.

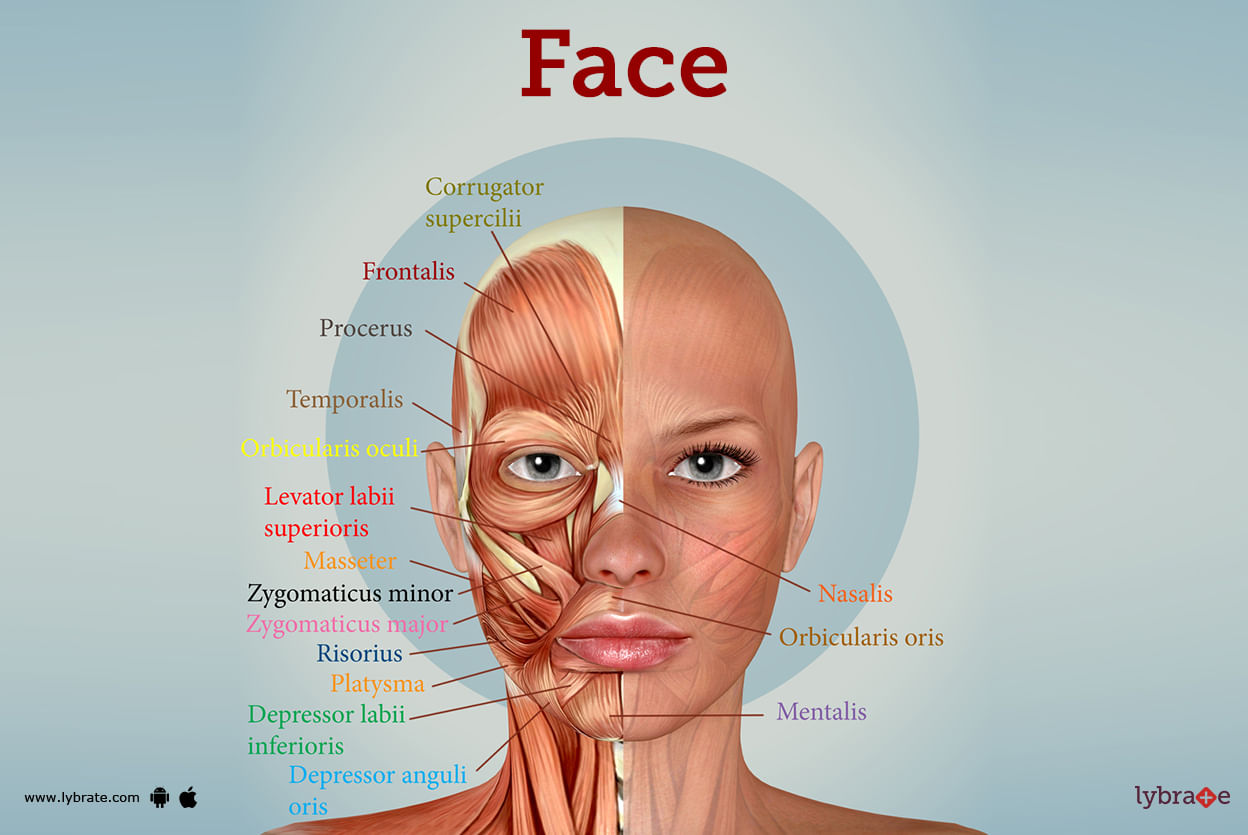

Identify Parts Of Pictures Diagrams And Photographs First Ca

Muscles Of Facial Expression The Axial Musculature Origin And

Face (Human Anatomy): Image, Function, Diseases, and Treatments